Never judge a princess (or anyone else, for that matter) by their gown.

They say girls turn pretty when they fall in love. But if they never fall in love, will they stay gross forever? Amars may not love flesh-and-blood real men, but they are in love with The Three Kingdoms and trains and dolls. What about them?

Mom, why do girls have to be pretty? Because I’d rather not. I’d rather not become pretty at all. Really.

—Kurashita Tsukimi, Princess Jellyfish Vol. 1

I finally had a chance to read the Vol. 1 Omnibus (Chapters 1-12) of Kodansha’s Princess Jellyfish (Kuragehime) manga, the story of a bunch of geek gals living together in Tokyo and the cross-dressing rich boy who befriends them. With its upbeat tone, cast of lovably awkward turtles, and celebration of female nerd counterculture, it’s easy to see why the series has charmed so many people.

Yet Princess Jellyfish isn’t all fluff and lightness: It isn’t afraid to touch on more serious topics (including, CW: the sexual assault of one of its male characters), and frequently acknowledges the real-world prejudices many of the characters face because they don’t conform to societal norms. It also isn’t afraid to show how those prejudices can be held by anyone, even those who face prejudice themselves.

Caution: Here There Be Spoilers for the Kodansha Omnibus Volume One (Vol. 1-2 of the original Japanese release). Please read responsibly.

The ladies of Amars (or “The Sisterhood,” depending on whether you’re reading the paperback or the CR Manga translation) are a delightfully diverse group of lady-nerds, with passions that vary from Chinese classic lit to Japanese dolls to the titular jellyfish. They’re depicted as by-and-large happy people, with fulfilling hobbies and friendships, a far cry from the “sad lonely nerd” so common in media.

Yet simply by living independently, unfashionably, and devoted to unconventional “true loves,” they’re committing a kind of rebellion, rejecting mainstream interests as well as traditional ideals of femininity (particularly in Japan, where women are still largely expected to become housewives and mothers) and are subject to scorn and stares. To combat this, they’ve carved out a refuge for themselves—the Amars House—where they can pursue their passions free from judgment.

Unfortunately, in the (understandable) process of protecting themselves from unfair societal standards, they’ve also walled themselves off from other people, limiting their worldviews and giving them their own set of biases. The Amars ladies struggle with self-confidence, which leads to a defensive “Us Versus Them” mentality that the Sisterhood sometimes uses to raise themselves at the expense of tearing down others—a mentality that Kuranosuke shines a light on when he saunters into their lives.

The Sisterhood initially fall into the trap of doing to Kuranosuke what others so often do to them: Judging him by his “Stylish” appearance and rejecting him on sight. They eventually warm up to him thanks to his generosity, confidence, and overall acceptance of their lifestyles, and in so doing he challenges their ideas about so-called Stylish people. Although, even then, Tsukimi still has to keep his gender identity a secret because Amars has such a hard-line stance against men.

The Sisterhood initially fall into the trap of doing to Kuranosuke what others so often do to them: Judging him by his “Stylish” appearance and rejecting him on sight. They eventually warm up to him thanks to his generosity, confidence, and overall acceptance of their lifestyles, and in so doing he challenges their ideas about so-called Stylish people. Although, even then, Tsukimi still has to keep his gender identity a secret because Amars has such a hard-line stance against men.

Kuranosuke serves as one of those rare, good examples of using cross-dressing as a way to challenge gender norms rather than reinforcing them, as the Sisterhood both accepts Kuranosuke and bans prospective tenants based on their (faulty) ideas about what it means to be a “woman” or a “man”—in essence, using the same cultural norms that have deemed them “rotten women (fujoshi)” to deem someone else fit or unfit for the Amars House. It’s all too easy to fall back on stereotyping and essentialism, rejecting discriminatory societal standards for oneself while insisting upon them for someone else (and thereby maintaining the status quo that’s hurting both groups). The Sisterhood are as susceptible to this habit as anyone.

Which isn’t to say Kuranosuke is a shining beacon of acceptance either, mind you. He’s drawn to Tsukimi and the Sisterhood because of their unique personalities and interests, but he also sees them as a “challenge” to his makeover skills, convinced every girl “wants to be pretty, deep down.” He mocks other characters for being virgins, rejects the title “transvestite” (or okama) because he’s “normal” (implying that being a transvestite is abnormal), and starts to view his previous, Stylish female friends as shallow and boring.

And that’s the thing: Everyone in Princess Jellyfish has these blind spots. Many have their roots in personal experience/trauma, some come from an ignorance that has no ill will behind it, while others are mean-spirited and actively destructive (please direct your attention to Inari Shouko, the woman who thinks it’s okay to drug, assault, and blackmail a man); but all contribute to the “othering” of different groups and the sharp social divisions that form the central conflict of the series.

No one in Princess Jellyfish is perfect. Everyone is both a giver and receiver of snap judgments and assumptions based on appearances. That’s what makes it such a fascinating and effective look at internalized prejudices and how cultural norms shape everyone’s ideas about each other.

Interestingly, where some series might reject society’s focus on appearances outright, going for an idealistic “eventually everyone will learn to love you for who you are, no matter what you look like” approach, Princess Jellyfish takes a more realistic/cynical stance (at least so far), acknowledging that sometimes, unfortunately, appearances do make a difference. With Amars in jeopardy and the Sisterhood struggling to fight back due to social anxiety and personal insecurity, Kuranosuke encourages them to “don the armor” of mainstream professional clothing and hairstyles so they’ll be taken seriously.

He makes it clear this is about public costumes and masks rather than changing one’s personality, which is vital. That the makeovers are ultimately about giving the Sisterhood confidence to go out and act naturally in public spaces, opening themselves up to new experiences, is vital, too. It’s a scene that could have easily fallen apart and is surprisingly empowering instead. Yet there’s still a question here about whether you can truly counter prejudice by taking on the guise of those who look down on you, and I’ll be curious to see if (or maybe how) Princess Jellyfish handles this tension in coming volumes.

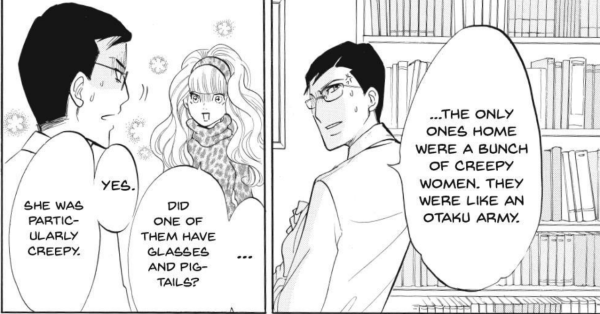

Certainly the battle between outward appearance and inner truth is going to be an ongoing struggle, given how many of the characters are leading “double lives,” accidentally or otherwise. Whether it’s the Sisterhood thinking Kuranosuke is a Stylish Woman, Shu thinking Tsukimi is both a Demure Lady and a Creepy Otaku, Tsukimi thinking Shu is a Cool Character, or the entire Japanese public not knowing their prime minister is a Theatrical Goofball, there’re enough misconceptions to fill a Shakespearean comedy at this point. Reveals are bound to happen eventually. How the series tackles them will tell us a lot about its ongoing goals.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Princess Jellyfish is, like its characters, very much an imperfect work as well. The series wants to celebrate women who don’t conform to social standards of love and beauty, but (like the Sisterhood themselves) it sometimes does this at the expense of women who do choose to live within those standards. There are no likable Stylish or married women in Princess Jellyfish so far; only voices on a phone whom Kuranosuke deems “boring” and Inari The Molester.

As a result, despite the series’ attempts (and many successes!) at challenging social norms and preconceptions, the “Us Versus Them” mentality implicitly remains, dividing, if not society as a whole (thanks to Kuranosuke), then women into Geeky Good and Stylish Evil. Given the way both sides treat sex and romance, this is just a hop, skip, and a jump away from a Madonna/Whore binary. It’s a concerning element, to be sure, along with the cast’s casual insensitivity towards LGBT people, although it’s hard to say yet if these are flaws with the story itself or with the individual characters. Either way, I do hope Princess Jellyfish works to address these issues as it goes.

Yet in a roundabout, accidental sort of way, even the manga’s own blind spots work to forward its central conversation about how everyone holds unwarranted biases, regardless of background or lifestyle, and how important it is to recognize and address that. As the characters’ prejudices are challenged through their interactions with each other, it throws a light on the story’s prejudices, and that ripples out to the individual reader as well. Where are my blind spots? What groups do I unfairly mock or snub my nose at?

If this past week has left me with anything (other than a crippling grief slowly turning into fury), it’s how easily latent prejudices can spiral into violent hate, and how quickly Awful Human Trumpster Fires will work to use the pain of one marginalized group to demonize and attack another. (That the attempts largely failed speaks to the staggering levels of compassion and strength coming from so much of the queer community, and gives me fistfuls of hope in the face of so much sadness.) It’s human nature to make snap judgments and harbor biases, even tiny ones, even seemingly harmless ones, but that doesn’t mean we can’t fight to overcome those instincts. In a lighter but still important way, Princess Jellyfish reminds us of this.

Between bouts of giggles at its goofy geekery, flashes of fierce protectiveness over these flawed, adorkable characters, and occasional squees at the budding romantic subplot, Princess Jellyfish‘s first volume encouraged me to consider the world beyond the page, and how I can work to become a more open-minded, accepting person myself. Warts and all, that’s an encouraging place for a series to be after just 12 chapters. I’m looking forward to seeing how its characters and conversations develop in the coming volumes.

Screenshots taken from the official Crunchyroll Manga translation. Quotes taken from the official Kodansha paperback translation. There may be some variations between the two.

It’s too bad the author’s later work was cancelled (well, technically suspended) because some people (men) complained it was derogatory to men. Sigh…

Anyways, I’m glad the first omnibus was a success for Kodansha USA, and I’m hoping the entire series goes to print. I want to collect them all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The author’s later work was cancelled (well, technically suspended) because some people (men) complained it was derogatory to men

Just looked this up, and gee, the whole thing sounds depressing and dumb as hell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know, right? It sounded so interesting and unique!

LikeLike

I feel like I’m not in love with series as much as most fans, Justin’s actually been hassling me to write up an editorial on it for OASG, and I’m glad that I’m not the only person who sees so many, simply put, problems with this story! I think it’s really interesting how so many geeky women really love this series and yet, it thinks that anyone outside of the Amars’ group is shallow and the Amars themselves aren’t portrayed with very much substance/care either! It’s a pretty prickly series for sure.

LikeLike

While I do agree PJ is by no means a perfect work (which has a certain value too, from a critical thinking standpoint), I’m not quite ready to write off the world outside of Amars just yet, especially since both Kuranosuke and Shu are, I think, pretty well-articulated characters. I’m fond of the Amars ladies, too, actually – they’re broadly drawn, but it’s a comedy so that’s not all that surprising, and at least they’re broadly drawn with variety, each woman with her own passion and way of expressing it. Plus I’m only 12 chapters in, so there’s plenty of room for the story to grow. (And if you’re deeper than that, please don’t tell me! I want to experience this as it unravels – with all its strengths and weaknesses – for myself.)

LikeLike

I don’t think this title will ever get licensed in my country (anything with explicit LGBTQ content is basically a no-go), so it’s neat to read such a detailed take to satisfy my curiosity on Higashimura’s work. Would love to see more manga stuff from you, this piece is such a lovely sample.

LikeLike

Thanks! To be honest, I don’t read a ton of manga (and when I do, I’m usually reading them months or years after they’ve been published), so I’ve struggled to find relevant topics to blog about. But I had a lot of fun with this one, so maybe I’ll try to work more manga (reading and writing!) into my schedule from now. Good to know you’d be interested in that too!

LikeLike